Introduction: The Historical and Theological Significance of the Johannine Comma

The Johannine Comma (1 John 5:7) has sparked considerable debate regarding its inclusion in the New Testament. This verse is pivotal for its clear articulation of the Godhead, a cornerstone of Christian doctrine. This blog post aims to defend the authenticity and importance of the Johannine Comma, tracing its presence in early manuscripts and highlighting its connection to the revered Christian tradition of Antioch.

Early Manuscript Evidence

Found in Ancient Writings

Contrary to the assertions that the Johannine Comma is a late addition by Erasmus, evidence points to its existence in manuscripts predating the 16th century. Notably, the Comma appears in several Latin manuscripts, attesting to its early acceptance within Christian scripture.

Latin Manuscripts and Marginal Notes

The inclusion of the Johannine Comma in Latin manuscripts, both within the scripture and as marginal notes, underscores its recognized theological significance early on. These manuscripts serve as a testament to the verse’s authenticity and its role in early Christian teachings about the Godhead.

The Byzantine Connection

Antioch: The Cradle of Christianity

The Byzantine text-type, associated with Antioch, plays a crucial role in our understanding of early Christian texts. Antioch’s significance is underscored by its historical distinction as the place where followers of Jesus were first called Christians. This connection emphasizes the importance of texts derived from or associated with the Byzantine tradition.

Byzantine Texts and the Johannine Comma

The Byzantine text-type’s relevance to the Johannine Comma debate is twofold. First, it represents a tradition of manuscript preservation that is closely linked to the early Christian community of Antioch. Second, its widespread usage and acceptance in the Christian world highlight the importance of considering its contributions to the biblical canon, including texts like the Johannine Comma.

In exploring the early manuscript evidence and the Byzantine text’s connection to Antioch, we uncover a rich tapestry of historical and theological reasons to defend the inclusion of the Johannine Comma in the New Testament. This foundational verse not only reflects the doctrinal truths held by early Christians but also connects us to the vibrant faith community of Antioch, where the name “Christian” first emerged.

Contrary to the assertions that the Johannine Comma is a late addition by Erasmus, evidence points to its existence in manuscripts predating the 16th century. Notably, the Comma appears in several Latin manuscripts, attesting to its early acceptance within Christian scripture.

Reevaluating Manuscript Primacy: Earlier Isn’t Always Better

The quest for the most authentic biblical text has led scholars to value earlier manuscripts as closer to the original writings. However, this assumption overlooks critical historical, theological, and textual considerations that challenge the supremacy of early manuscripts.

The Missing Verses: A Critical Overview

In examining the textual variances, it’s noteworthy that several verses present in the Byzantine text-type and included in the King James Version are absent in the older Alexandrian manuscripts. These omissions include:

- Matthew 17:21

- Matthew 18:11

- Matthew 23:14

- Mark 7:16

- Mark 9:44, 46

- Mark 11:26

- Mark 15:28

- Luke 17:36

- Luke 23:17

- John 5:4

- Acts 8:37

- Acts 15:34

- Acts 24:7

- Acts 28:29

- Romans 16:24

The absence of these verses in older manuscripts raises questions about the criteria used to determine textual accuracy and authenticity.

Geographic and Theological Contexts: Alexandria vs. Antioch

Origins of Manuscripts

The older manuscripts often cited to challenge the inclusion of certain verses, including 1 John 5:7, primarily come from the region around Alexandria, Egypt. This area was known for its allegorical interpretation of Scripture, championed by figures such as Clement of Alexandria and Origen.

The Influence of Alexandrian Theologians

- Clement of Alexandria: Allegorized biblical dietary laws, interpreting them as moral injunctions rather than literal food restrictions.

- Origen: Applied a threefold sense to Scripture (literal, moral, spiritual), often spiritualizing texts, such as interpreting the Parable of the Good Samaritan as an allegory for the soul’s journey.

- Athanasius of Alexandria: While less focused on allegory, contributed to doctrinal debates, emphasizing deeper spiritual meanings within the scriptural narrative.

- Cyril of Alexandria: Saw Christological significance in Old Testament passages, often beyond the literal historical context.

These interpretations, while enriching the theological tapestry, sometimes deviated significantly from the literal text, influencing the theological environment from which the Alexandrian manuscripts emerge.

The Historical Testimony of Corruption

Apostolic Warnings

Paul’s admonition in 2 Corinthians 2:17 (KJV) starkly warns of the corruption of God’s word: “For we are not as many, which corrupt the word of God: but as of sincerity, but as of God, in the sight of God speak we in Christ.” This statement implies that even in the apostolic era, there were attempts to alter or misinterpret the scriptures.

Implications for Textual Criticism

Paul’s warning underscores a crucial point: the existence of corrupt practices from the earliest days of Christianity. This historical reality challenges the presumption that earlier manuscripts are inherently more accurate or faithful to the original texts.

Conclusion: A Case for Caution and Respect for Tradition

The distinctions between Alexandria and Antioch, both in geographical origin and theological interpretation, along with the apostolic warning about corruption, compel us to approach the evaluation of manuscripts with caution. While older manuscripts offer invaluable insights, their age alone does not guarantee superior accuracy or fidelity to the apostolic teachings. The Byzantine text-type, associated with Antioch, deserves consideration not just for its historical breadth but for its transmission within a community closely tied to the earliest followers of Christ.

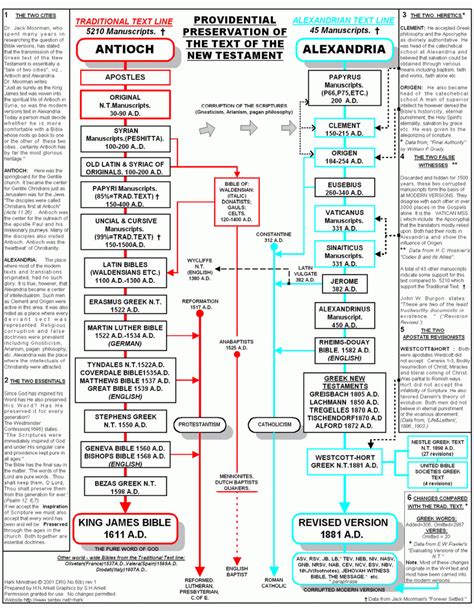

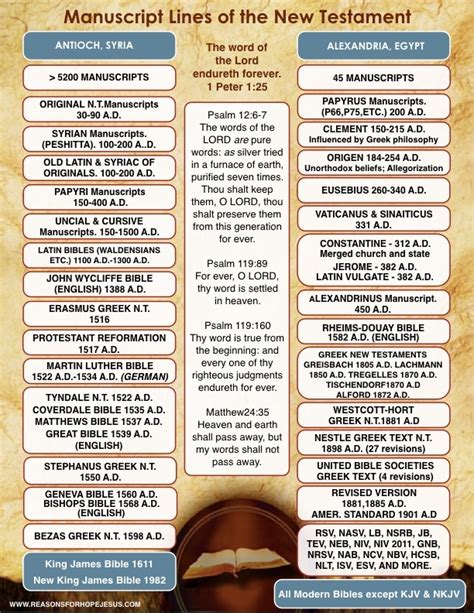

The Testament of the Majority Text: Consensus versus Variation

The textual landscape of the New Testament manuscripts is marked by two primary families: the Majority (or Byzantine) text-type and the Alexandrian text-type. A closer examination of these textual families reveals significant differences in consistency and agreement among the manuscripts.

Unity in the Majority Text

The Majority text-type, as its name suggests, comprises the vast majority of Greek New Testament manuscripts. This textual family is characterized by a remarkable consistency across its manuscripts, which span different geographic regions and centuries. The coherence within the Majority text suggests a high degree of transmission fidelity among the communities that copied and circulated these texts.

Example of Consistency

A clear instance of this consistency is found in the handling of the doxology of the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew 6:13. The Majority text uniformly includes the phrase, “For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever. Amen.” This inclusion reflects a common tradition across a diverse array of manuscripts within the Byzantine text-type.

Variability in the Alexandrian Manuscripts

In contrast, the Alexandrian text-type, represented by a smaller collection of manuscripts, exhibits more variation within its family. While some of its manuscripts are among the oldest accessible, their agreement with each other is not as consistent as that observed in the Majority text.

Example of Variation

A notable variance occurs in the account of the Agony in the Garden found in Luke 22:43-44, where an angel strengthens Jesus, and He sweats drops of blood. Some Alexandrian manuscripts omit these verses, reflecting a lack of uniformity within this text-type about their inclusion.

The Implications of Textual Diversity

The differences in agreement among the manuscript families have profound implications for textual criticism and the reconstruction of the New Testament text.

- The Strength of Consensus: The uniformity within the Majority text supports its reliability as a witness to the original text. The widespread geographical distribution and temporal span of these manuscripts underscore a consistent transmission of the text.

- Challenges of Variation: The variations within the Alexandrian manuscripts present challenges for establishing a definitive text. While some argue that the older age of certain Alexandrian manuscripts may reflect a closer approximation to the original, the discrepancies among these manuscripts complicate this assertion.

Conclusion: Navigating Textual Traditions

The contrast between the Majority and Alexandrian text-types underscores the complexity of the New Testament textual tradition. The Majority text, with its broad agreement across a wide array of manuscripts, offers a compelling testament to the stability of the New Testament text over time. In contrast, the variability within the Alexandrian text-type serves as a reminder of the textual fluidity in the early centuries of Christianity. This analysis invites a careful consideration of all textual evidence, encouraging a nuanced approach to reconstructing the most accurate text of the New Testament.

Embracing Tradition and Trust: A Call to Rediscover the King James Version

In the journey through the complex terrain of biblical manuscripts, textual types, and the rich history of early Christianity, it’s easy to see how debates over verses like 1 John 5:7 can leave believers feeling uncertain about which version of the Bible to trust. However, the King James Version (KJV) offers not just a translation of Scripture but a testament to the enduring power of God’s Word through the ages.

The Case for 1 John 5:7 and the KJV

The inclusion of 1 John 5:7 in the KJV reflects a tradition that values the testimony of the Majority text-type and its connection to the early Christian community of Antioch. This verse’s presence in the KJV, supported by historical practices and theological understandings, invites us to reconsider its significance in the doctrine of the Godhead.

Beyond Scholarly Consensus: A Matter of Faith

While modern scholarship and critical text editions offer valuable insights, they do not hold the final word on the authenticity of Scripture. The debates surrounding the Alexandrian and Byzantine text-types, and the varied interpretations offered by church fathers from Alexandria, underscore the necessity of approaching biblical texts with both critical thought and faith.

Investigating with Open Hearts and Minds

Christians are encouraged to delve deeper into the history and textual traditions that underlie different Bible versions. Understanding the nuances of these traditions, especially the distinctions between texts associated with Alexandria and those from Antioch, can provide valuable context for why certain verses, including 1 John 5:7, appear in some texts and not others.

Trusting in God’s Preservation of His Word

The history of Scripture’s transmission is a testament to God’s promise to preserve His Word. The KJV, with its reliance on the Majority text-type and its historical roots in the faith community of Antioch, stands as a beacon of this promise. Christians can trust in the KJV as a faithful vessel of God’s enduring message.

A Final Word of Encouragement

Let this exploration serve as an invitation to reengage with the King James Version of the Bible. In doing so, you’re not merely choosing a translation; you’re embracing a rich tradition that has carried the words of God through centuries. The presence of verses like 1 John 5:7 in the KJV is a reminder of the depth and diversity of Christian textual history, urging believers to trust in the divine guidance that has preserved Scripture for generations. As you continue your journey with the Bible, let history, tradition, and faith guide you toward a fuller understanding of God’s Word and His promises.